REFERENCES AND NOTES

1 See the Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society xv (1909) pp. 84-85; also xiv, p.70.

2. The printer, Mr D Trimble of The Guardian, Armagh, presented a copy of the pamphlet to the National Library in Dublin, and in the library index and in several bibliographies of Irish Genealogical sources he is mistakenly named as the author of the pamphlet; indeed sometimes the pamphlet is listed twice under both Shannon and Trimble.

3. Admittedly there is a James Kingston entry amongst the Co. Cork purchasers of land in 1702, according to the lists in John O'Hart, The Irish and Anglo-Irish Landed Gentry When Cromwell Came to Ireland, Dublin 1884, p 519, but an inspection of The Book of Postings and Sales of Forfeited and Other Estates and Interests in Ireland, Dublin, 1703, shows that this is a misreading of the name James Hingston, the two surnames not infrequently being confused.

To avoid further confusion it may be added that the name Lord Kingston or Earl of Kingston appears regularly in the records of land transactions of this and later periods, but this prominent landlord family of Mitchelstown Caste, Co. Cork, had no relationship whatever with those surnamed Kingston, their surname being King. The Kingston title dates from 1660 when John King of Boyle, Co. Roscommon, was created Baron Kingston. Mitchelstown Castle was destroyed in 1922 but the oddly named Kingston College, consisting of homes for those in need, is still in used nearby.

4. See Wm. Maziere Brady, Clerical and Parochial Records of Cork, Cloyne and Ross, London, 1864, vol i. p. 104; also Henry Cotton, Fasti Ecclesiae Hibernicae, Dublin, 1847-60, vol. i, p. 216.

5. Surprisingly these Kingston appointments are all found in the first half of the fourteenth century, with no record of the name in the following centuries:

1306 Nicholas de Kyngston, Canon of St Patrick's Cathedral.

1332 Death of John de Kingston, Incumbent of Dunganstown or Inishbohin.

1325 John de Kyngeston, Prebendary of Aderk. Presumably identifiable with John de Kyngeston, a Canon, appointed a Guardian of the Spritualities of the archdeaconry of Glendaloch in 1328.

1349 Adam de Kingston, Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral. It is surmised that he was appointed as the local nominee in 1346 but replaced by the Pope's nominee in 1349, when he moved to Castleknock parish. In the list of Deans displayed in the cathedral the only date given for him is 1349.

See Henry Cotton, op. cit., vol. ii, pp. 92 and 193; H. J. Lawlor, The Fasti of St. Patrick's, Dublin, Dundalk, 1930, pp. 16, 40, 93, 95 & 120.

6. Some lists of tenants in the Boyle estates are included in The Lismore Papers, e.g. MS 6139 re Bandon etc., but we haven't found any Kingstons in these lists.

7. See M.S.S. of Earl of Egmont, vol. i, Part i, pp. 248 & 315.

8. The primary available documentation on these land transactions is found in the Books of Survey and Distribution, large manuscript volumes covering the period from Cromwell to the end of that century (the Annesley copy being consulted), and also in the Appendix of, and References to, the Principal Records and Public Documents connected with the Acts of Settlement and Explanation' in Irish Record Commission Reports, 1811-1825, vol. iii, London, 1825.

9. These were two Kingston Adventurers, Felix, a stationer of London (and probably identifiable with Felix, one of the King's printers in Ireland in 1628), who advanced £100 but died in 1653 before he could settle in Ireland, and John, possibly his son, who is omitted in some lists of Adventurers. In the lots they drew land in Co. Meath.

The only Kingston soldier, apart from Samuel of Skeaf, was Ensign Humphrey Kingston, a 'Forty-nine Officer' (i.e. he had served in Ireland before 5 June 1649) who received house property in Dublin. This entry is doubtful, however, as we find an Ensign Humphrey Kinaston in one army list. There is also a very vague reference to Kingston, with no forename or other details, in one index of soldiers etc., which remains inexplicable.

According to the pedigree of the Kingstons of Co. Laois and England in the offices of the Society of Genealogists, London, the first member of that family in Ireland was a Capt. John Kingston, a Cromwellian soldier granted land in Queen's Co. We can find no documentary record of such a grant, and the fact that the family tree jumps from Capt. John Kingston to his grandsons shows some vagueness about their origins in Ireland.

10. Seamus Pender, ed., A Census of Ireland circa 1659, Dublin 1939, p. 214.

11. Ibid., Preface.

12. Although Carbery is mentioned in the Act of Satisfaction of Sept. 1653 as one of the additional baronies to be used if necessary for the 'satisfaction' of the forces then about to be disbanded it is evident from an order issued on 10 May 1655 that both East and West Carbery were 'as yet undisposed of to the said disbanded soldiery' almost two years later (see R. Dunlop, ed., Ireland Under the Commonwealth, Manchester, 1913, pp. 507-8). The next major disbanding took place in August of that year, but if Prendergast, who oddly refers to it as 'the first and largest of the three great disbandings of the army', gives the complete list of the baronies involved then the absence of Carbery must mean that it wasn't planted until the July or Nov. disbandings of 1656. (See J. P. Prendergast, The Cromwellian Settlement of Ireland, 3rd ed., Dublin, 1922, pp. 216-20 & 226). By that time the distribution of available land had been handed over to the officers, who appointed trustees to act on their behalf, but unfortunately no record of how they allocated areas to the various sections of the army survives (see Dunlop, op. cit., pp clvi ff.). Records of individual grants are of course known from later enrolments.

13. As Co. Cork was not amongst the counties somewhat reluctantly assigned for the satisfaction of the Munster garrisons, and as these soldiers were reported to be still waiting for their allocation of land at the time of the Restoration in 1660, it would seem that a grant in Carbery during or before 1659 could not be for service in Munster. There is ample evidence, however, that some members of these garrisons did receive land in Co. Cork, and moreover received it before the Restoration. Colonel Widnam of Youghal, for instance, got land in Fermoy, and is stated to have 'kept it after the Restoration' (Prendergast, op cit, pp. 193-4). More significantly Dashwood got land in Carbery, and all of them are listed as residents in West Cork in the 1659 Census (Bayly spelled Braily).

14. At an earlier stage in the Civil War between King Charles I and the Parliamentarians Lord Inchiquin had revolted from the side of the King to Parliament, but in 1648 he reverted to the King, and hence the Munster garrisons were actually opposed to Cromwell when he landed in Dublin the following year. Those, however, who played an active part in the surrender of these garrisons to Cromwell in November 1649 and who continued to serve under him, thus proving their 'constant good affection', were pardoned for their action in 1648, and like the rest of the army were to receive land for their arrears of pay.

15. See Bennett, op. cit., p 473 and Prendergast, op. cit., p. 193.

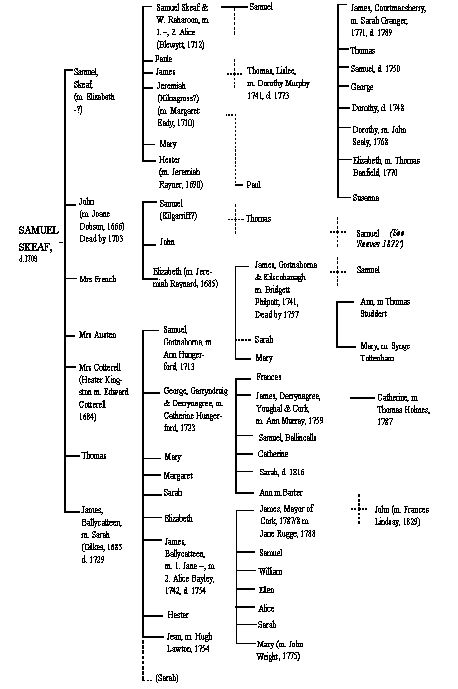

15a. The argument in this section isn't invalidated by an apparent confusion in the Townsend biography between the Kingston and King (John Baron Kingston) families, nor by the inaccuracy of the statement that John Townesend (Col. Townsend's grandson) was sovereign of Clonakilty in 1710. In fact John Honner was sovereign in 1710-11, and admitted not only James Kingston but also John Kingston, Samuel Kingston and Samuel Fitzjames Kingston as freemen that year (see "Notes on the Council Book of Clonakilty", collected by Dorothea Townshend, in JCHAS, vol. 2 (1896), p. 31). It wasn't until 1720 that John Townesend became sovereign, admitting Samuel Kingston of Kilgarrif as freeman (ibid., p. 132). These five Kingstons are presumably identifiable on the Skeaf chart as James (senior) of Ballycatteen, John son of John, Samuel of Skeaf & W. Raharoon, Samuel of Gortnahorna ("Fitzjames" being "son of James") and "Samuel (Kilgarriff?)" respectively, and hence they are not mentioned in the sectionon "Other and Possibly Unrelated Co. Cork Kingstons" which does consider the only other Kingston in the Clonkilty Council Book Extracts, namely William of 1707.

Incidentally Dorothea Townshend's hesitancy about identifying Colonel Townsend's second wife in the 1892 biography has vanished by 1895 when she explicity named her as Mary Kingston in her comments on the Council Book of Clonakilty (see JCHAS, vol. 1 [1895], p.390).

16. We are assuming that Townsend's fifth son Kingston was probably the first son of his second marriage. His date and place of birth are unknown but the next son was born at Kilbrittain Castle in 1664. A 1666 deed signed by Mary is mentioned in Townsend's biography. Family tradition names Hildegardis Hyde as the mother of Townsend's second son Bryan, reputedly born at Lomsale in 1648, but no details are available concerning other births until 1664, nor is it known when the first Mrs. Townsend died.

17. The only Kingston named under the Act was a 'Gent' of Knocktopher, a barony in Co. Kilkenny. Not even his forename is given, just 'Kingston'.

18. See Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the Reign of William and Mary, May 1690-Oct. 1691, London, 1893, p 213.

19. Bennett, op. cit., p.292, names four persons, three of them colonels, amongst the West Cork exiles who returned to Ireland with William III, but they do not include a Col. Kingston. The list is only a sample, however, and hence his silence about the name is not really significant.

20. See Brady, op. cit., pp. 114-15.

21. Lieut. Toby Mulloy is also credited with giving his horse to the King when William's charge was allegedly shot-- see Mulloy pedigree in Burke's Commoners, iv, pp 146-50.

22. See J G Simms, Jacobite Ireland 1685-91, London, 1969, p. 150: "William... himself crossed there with Inniskilling, Dutch and Danish cavalry. His horse was bogged down....'

23. (1) Thrift abstracts of the wills of Samuel Kingston, Skeaf, d.1703, his son James, Ballycatteen, d.1729; Thomas Kingston, Lislee, d. 1773, his son James, Courtmacsherry, d.1789. All that in the P.R.O. Dublin.

(2) Fisher abstract of the will of James Kingston, junior, Ballycatteen, d. 1754. Genealogical Office, Dublin. (Some of these wills also in Burke's Pedigree Charts).

(3) Kingston deeds in Registry of Deeds, Dublin, and some in possession of Mr S. E. Kingston of Dublin.

(4) Index of Marriage Licence Bonds, Diocese of Cork and Ross, 1623-1750, in P.R.O. Dublin, and also as published by H. W. Gillman, Cork 1896-7. Also Index of Cloyne Diocese. Incidentally, not all the Skeaf Kingston marriages, e.g. of son Samuel or of unnamed daughters to Austen and French, are in the Index.

(5) Kingston section of family-tree of Mrs Constance Pole Bayer of Miami, Florida.

(6) 1893 article and 1929 pamphlet on 'The Kingston Family in West Cork'.

(7) Rosscarbery Parish Registers, from 1713.

Of these the abstract of Samuel's will of 1703 is the most informative, giving the names of (presumably) all his surviving grandchildren, and indirectly the name of his dead son John, but not giving the forenames of his three married daughters. The three youngest children of his son James are omitted, probably not yet born in 1703, and these are added to the chart from the abstract of James' will. This, in fact, omits Mary, places James third and Sarah last, suggesting that by 1729 Mary was dead and also Sarah, a further daughter having been born and given the name of her dead sister. Unhappily all but two members of the family of George of Garryndruig and Derrynagree have to be taken at second-hand from Mrs Pole Bayer but nearly all other details are based on primary sources. Precedence is given to Thrift abstracts in resolving minor clashes of evidence with 'The Kingston Family in West Cork' article.

24. The assumption that Samuel of Gortnahorna had only one son is based on the description of his daughter Mary as his 'only surviving issue' in a 1768 deed, her brother James having died about ten years earlier, but strictly speaking this description does not preclude the possibility of other dead brothers, some of whom could even have been survived by their offspring, though this is not likely.

25. See W. P. W. Phillimore, ed., Indexes to Irish Wills, London, 1910, vol. ii, p.64.

26. Index of Administration Bonds, 1630-1857, Diocese of Cork.

27. Ibid.

28. See also the half-page article on Kingston in his More Irish Families, Galway & Dublin, 1960, which mentions Bandon as another area where Kingstons can be found 'in strength', and expresses doubts about the all-Kingston roll at Meenies school.

29. There is an index to Kingston (unfortunately including numerous Lord Kingston, i.e. King family) deeds in the Registry of Deeds, the vast majority of the Kingston-surname deeds dealing with the Skeaf family. It is sufficient here to note the numbers of just a few of the more important deeds substantiating contacts: 11235, 92912, 96799, 75075, 126272, 177162 and 213840.

30. One serious though understandable error was the assumption that her ancestor James of Derrynagree, Youghal and Cork was Mayor of Cork in 1787, confusing him with his first cousin of the same name. This error is repeated in her privately published book And in the New World, 1968, p.82.

31. Those attending the earliest recorded Church Vestry meeting on Easter Tuesday 2 April 1782 (which 'resolved unanimously that the sum of eighty pounds be raised.... towards the building a new Church at Dromdaleague') included Paul Kingston, Church Warden, and also Thomas and William Kingston, that is, three Kingstons amongst the eight to ten laymen present (the total being uncertain as the end of the page is worn). No townlands are specified, the earliest locatable Kingstons in these minutes being Paul of Gurteeniher, 1786, Samuel of 'Moynies', 1789, and Paul of Clodagh, 1795, each being Church Warden at the time.

32. JCHAS xxxv (1930) p. 100.

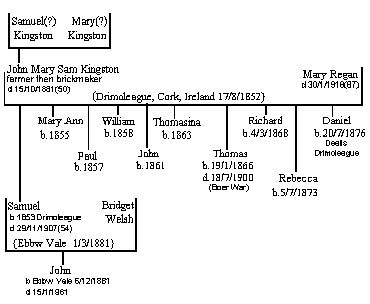

33. Known locally as 'Sam Paul Mary', but he himself was adamant that he was really 'Sam Paul Sam Paul Sam', and this pedigree can be verified except for the final Sam, that too being perfectly credible as he had presumably been told that the grandfather he never met-- a victim of the famine-- was called 'Sam Paul Sam'.